We are in the last 72 hours of existence of the online radio station that got me through Covid, spurred me to learn about a new genre of music, and partially inspired my latest still-to-be-published book. Goodbyes have been said to our favorite hosts; now it’s just what they call the “jukebox” of random songs on one channel, and business as usual on the other (reruns of Jesse Dayton’s shows and more jukebox). As has been my habit now for almost three years, I’ve had that second channel (Jesse Dayton’s) on while I’m working. But I just peeked over to the main channel’s chat room, and there are still people determined to hang in till the bitter end. And some probably will, until 1:00 AM on Sunday when the schedule for the station ends and it’s supposed to shuffle off the Internet coil.

This is not my first radio rodeo. Since I was about 10, there’s always been some station or other that I’m hooked on (first terrestrial radio, more lately Internet). At some point their management betrays me, and they go out of business or switch formats or something. And then I move on.

This one’s bugging me a lot, and I realized I’ve been getting more and more frustrated each time it happens. Because at a time when we have more access to more kinds of music, 24/7, than at any time in history, I know what I will really be missing: curation and community.

The station I’m about to break my heart over is Gimme Country Radio (part of Gimme Radio, which also included Gimme Metal—I just heard they were about to have a punk option as well before the rug got pulled out). The reasoning is that they intended this thing to be successful and scale up. They accomplished the first goal. This station had the kind of loyal following any business would dream about; an audience used to spending lots of money on anything music-related, happy to buy up GC merch and throw money in the tip jar. (Most of the DJs were unpaid volunteers, often musicians who couldn’t tour during Covid; tips helped them along.) The chat rooms were vibrant and funny; and I never experienced the kind of trolling crap I see virtually everywhere else humans gather online.

But the venture was funded by, guess what, venture capital. Two words (that along with “private equity”) send a shiver up my spine and throw my brain into rage mode. The operation had expansive goals that depended on the funding; in turn the funders expected the goals to be met before coughing up more. Never mind that Gimme had found a successful niche where it could have cruised forever; it had to DO MORE, keep moving or die. And when it couldn’t do that fast enough, the money spigot turned off. Venture capitalists have other fish to fry, after all. Things that benefit actual people are low on the list, what with shooting cars and billionaires into space and cryptocurrency and NFTs and a bunch of other shit that is basically financial masturbation for a few people at the top.

So bye bye Gimme.

The last time I went through this was about 15 years ago. No, back up: It was around 2005. The terrestrial radio station I listened to often, Y100 in Philadelphia, went down. Terrestrial radio doesn’t give you weeks to say goodbye in the chat room. It happens immediately. One minute your usual hosts and music are on the air; the next they’re being yanked off. Y100 (a “modern rock” station) was an admittedly commercial and imperfect enterprise that was Philly’s main alternative to the tiresome rock and classic rock giants, a successor to a more quirky and smaller station from the 1990s, WDRE, which I could only catch infrequently and imperfectly in the car. So for a while there, even if they were basically commercial radio, I had a place to hear something besides endless Led Zepelin. (The radio version of the Bechdel test is, can you turn a station on randomly any time of the day or night and hear Led Zeppelin? That station is probably crap.) Anyway, Y100 did get a few hours of farewell, which the DJs used to program free-form. I got to scream along with the Distillers’ “City of Angels” as I drove home from work; for a minute there I thought I’d ruptured something in my throat.

Y100’s former program director, Jim McGuinn, and some of his staff immediately formed an underground online station, Y100Rocks. Unfortunately, I didn’t hear about it right away and went through a couple years of radio hell/withdrawal/Pandora. Around the time I finally heard about it, they got taken over by Philly’s great public radio station, WXPN, from the University of Pennsylvania. Now, I like and support WXPN. They are great. My go-to car station. But they are a LITTLE heavy on the singer-songwriters who all sound alike to me, and they didn’t used to have much rock. (They have somewhat more nowadays.) So for a few years what had been rechristened Y-Rock trundled along as an online/HD2 station. (Remember when that was supposed to be a thing? I bought a new stereo system just for the HD2 radio, which never worked properly). Mostly volunteer DJs, great programming, and even a punk show that helped inspire me to start writing and going to shows and got me through a major depressive episode. In fact, winning tickets to see Mike Ness in 2008 from Y-Rock was what first got me going back to shows, after a decades-long drought. It made me realize I could.

In 2010, though, WXPN decided to drop Y-Rock. I got into a Facebook fight with their GM, whom I accused of “eating the seed corn” and relegating WXPN back to a bunch of old fogies (people my age) and driving away the youngsters they needed to grow. They must have taken it under advisement because they did not abandon rock completely, but they still skew older. The Y don’t die, though. McGuinn had left in 2009 (probably one reason WXPN lost interest), but his unquenchable former employees Josh T. Landow and Joey O formed another entity: Y-Not Radio, which exists to this day. It exists, precariously through subscribers (I’m one, though I admit I don’t listen as much as I used to, having gotten far into punk, country, and Americana) and donations. Josh has kept it going by not overreaching: It does what it does, and that’s more than enough for its loyal listeners. No need to kiss up to venture capital, but it also means a mad scramble at the end of the month to pay the bills.

I got into Gimme right when things were swirling around for me. First several months of dealing with a health crisis of my husband’s, then we had just gotten back to work when Covid came down. I went to my last show for 15 months the night before lockdown, and now it looks prescient: Brian Fallon (of The Gaslight Anthem, a punk-adjacent band I discovered and went mad for on Y-Rock), with the late Americana/country musician Justin Townes Earle opening. (It would be Justin’s final show; he died in August of 2020.) My past and future, though I didn’t know it. And it gets even weirder: Let’s go back to that Mike Ness show, in 2008. When I won those tickets from Jim McGuinn of Y-Rock. The opener for that show was Jesse Dayton. I was instantly taken with him and his music, and have seen him several times since. He opened for John Doe on one tour and for Jonny Two Bags of Social Distortion on another, and also filled in for Billy Zoom of X when Billy was being treated for cancer. Somewhere along the line I met and spoke to him a couple of times.

I followed Jesse on social media, and eventually saw he was hosting this show called The Badass Country show on an online station called Gimme Country. And during Covid I decided to start tuning in.

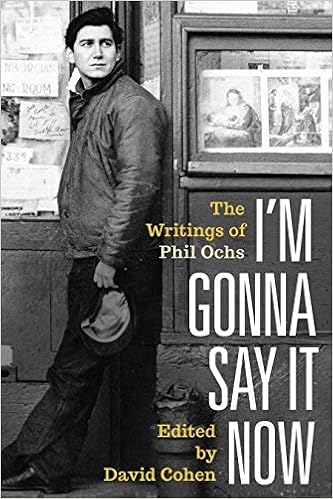

What I found (in addition to an excellently curated show that “country” doesn’t even begin to describe) was a lively community of folks in the chat room who, while they might identify as primarily country or Americana fans, also knew, loved, and listened to all kinds of music. Jesse played a lot of blues (and I finally learned the differences between different types of blues), jazz, country, folk, rock, rockabilly, punk, and pretty much everything you can think of on the show. I explored some of the other shows on the station, many hosted by musicians like Jesse who had been idled by Covid. Literally any kind of music you ever wanted to hear or explore was there somewhere. Jesse’s bass player and a successful musician in his own right, Chris Rhoades, started a cool rockabilly show that would have saved me so much research when I was writing Arboria Park. Guest DJs, even some of my punk folks, drifted in and out doing specials. Wednesday at 5:00 p.m. was always the new weekly Badass show; I put everything down to hang in the chat room whenever I could. (My name there was WhenSheBegins, a Social D reference.) I listened to the repeats and caught up on interviews I’d missed before I started listening when Gimme started a second channel, the Jesse Dayton Station. I’d throw that on while I worked or cleaned to hear old favorites and learn new musicians to check out. Because of Jesse, I started adding more Americana shows to my schedule once things started up again. I’d always made time to see Steve Earle, Lucinda Williams, Dave Alvin, or Lucero, but now I added some new folks like the Vandoliers or Joe Pug, whom Jesse played and interviewed. One reason I had started listening was because he was interviewing people I already loved like Rosie Flores, Johnny Hickman, and Jonny Two Bags, but he introduced me to the music of Robert Ellis, Garrett T. Capps, Trent Summar, and many others. (Although I told Jesse yesterday, during the chat room farewell party, that probably the most unexpected highlight was learning about Jon Wayne and hearing “Texas Funeral” during a Texas-themed show.)

And I have Jesse to thank for starting to play guitar and write songs. The songs came first, during Covid, as I was hitting the wall. I also had gotten this urge to buy an electric guitar. I searched Facebook Marketplace for one while I wrote a few songs I needed to find a way to get out of my head. The first few were just things of mine, but a few started coming out in a voice I didn’t recognize at first.

I’ve realized I need four things to write a novel. An inciting incident, a piece of local history, some trauma of my own, and a soundtrack. When I had a mammogram go sideways right in the middle of the songwriting and the Fender online guitar lessons, I became (fortunately temporarily, for the moment at least) a member of the cancer-fighter community. I got to walk into “the Helen” (the Helen Graham Cancer Center) at my local hospital and stare at a name on the donor plaque in the lobby. The name of the company my grandfather worked for in West Virginia, headquartered here in Delaware. The one that got sued twice (and lost) some years back for poisoning the air, land, water, and people of West Virginia. Including everyone in my mother’s family, who all had different kinds of cancer and autoimmune diseases. I’ve inherited the beginnings or precursors of all three of the ones my mother had. One of my other Covid hobbies had been insulting Senator Joe Manchin on Twitter (in addition to his politics, his family and mine have some, uh, personal business), so much so that my phone started pushing West Virginia news at me. I haven’t been back since 2003 and in the travel-deprived days of Covid I craved a trip there. My brother and I were doing a lot of family research at the time as well. And gradually I realized the voice of those songs I didn’t recognize was a girl in West Virginia near where my mother’s family had lived. A girl whose father had been a successful country star back in the 1990s, a contemporary of Garth Brooks and Steve Earle who had torched his career, fortune, and marriage to go back to West Virginia and spend 15 years unsuccessfully trying to sue the chemical company that had poisoned his hometown. And I had the novel, in one fell swoop. I started writing it two days before my lumpectomy and finished it a little over a year later. It’s structured around Steve Earle’s songs, and has an extensive playlist. Some of the songs are ones I have long been familiar with, and others I learned about from Jesse Dayton and the people in the chat room.

When I get that baby published, you can bet your ass I will be thanking Jesse and the chat folks in the acknowledgements. The playlist at the end will be for them.

Some of the chat folks have started a Facebook page. We all have shows to go to. We’ll struggle on.

But Wednesday won’t be the same for me. I still have my old friends WXPN for a variety of singer-songwriters and Y-Not for current indie rock. The otherwise execrable big Philly rock station has one evening DJ who just goes crazy on Friday nights and plays nothing but requests and his own arcane favorites, going WAY off the normal playlist. My husband still listens to Pandora and urges me to. I suppose I could grudgingly start listening to Spotify, though it is part of the problem and not a solution. There’s YouTube and a million other places to find music if I want.

But there are few places where musicians and audience can connect directly. I thought this was primarily a punk thing where it did sometimes happen. But it also happened on Gimme. Many of the DJs were the kinds of musicians who need to be on the road, interacting directly with fans so they’ll buy T-shirts that will enable the musicians to get gas money for the next gig. We all interacted together, sharing inside jokes and artist recommendations and stories of musical adventures. The afore-mentioned Vandoliers also had a Gimme show, and they’ve now moved to doing one on Spotify. But one dropped into the chat room last night to lament that there’s no chat function or real-time interaction there, so it’s not the same for them or for the listeners.

So Gimme sails into the sunset this weekend, after the online schedule goes dark. There was a debate in chat last night over whether we should delete our user profiles before it does. I said they’d have to pry mine out of my cold dead fingers. Many others agreed; we’re going down with this ship. It’s the one who picked us all up off whatever island we’d been stranded on and gave us a free-wheeling 24-hour Outlaw Country Cruise that seemed like it would never end. Now we’ll go our separate ways, but I’ve noticed as various folks sign off, they all say the musician’s farewell: “see you down the road,” not goodbye. Right now Guy Clark’s “LA Freeway” is playing on Gimme; I wonder what the last song played will be. (Edit: Never mind, I know. They just played it six times because they can and then the app went down on my phone. Getting “Wasco”ed is like getting Rickrolled):